Pyramidal-Interneuron Gamma network

Pyramidal-Interneuron Gamma network

Jupyter Notebook: Please work on

PING_circuit.ipynb.

Introduction

This tutorial provides a simple example of how to use the Neuroblox package to simulate a pyramidal-interneuron gamma (PING) network. These networks are generally useful in modeling cortical oscillations and are used in a variety of contexts. This particular example is based on Börgers, Epstein, and Kopell [1] and is a simple example of how to replicate their initial network in Neuroblox.

Conceptual Definition

The PING network is a simple model of a cortical network that consists of two populations of neurons: excitatory and inhibitory. We omit the detailed equations of the neurons here, but note they are Hodgkin-Huxley-like equations with a few modifications. Excitatory neurons are reduced Traub-Miles cells [2] and inhibitory neurons are Wang-Buzasaki cells [3]. Both follow Hodgkin-Huxley formalism, i.e., the membrane voltage is governed by the sum of the currents through the sodium, potassium, and leak channels, along with external drive, such that:

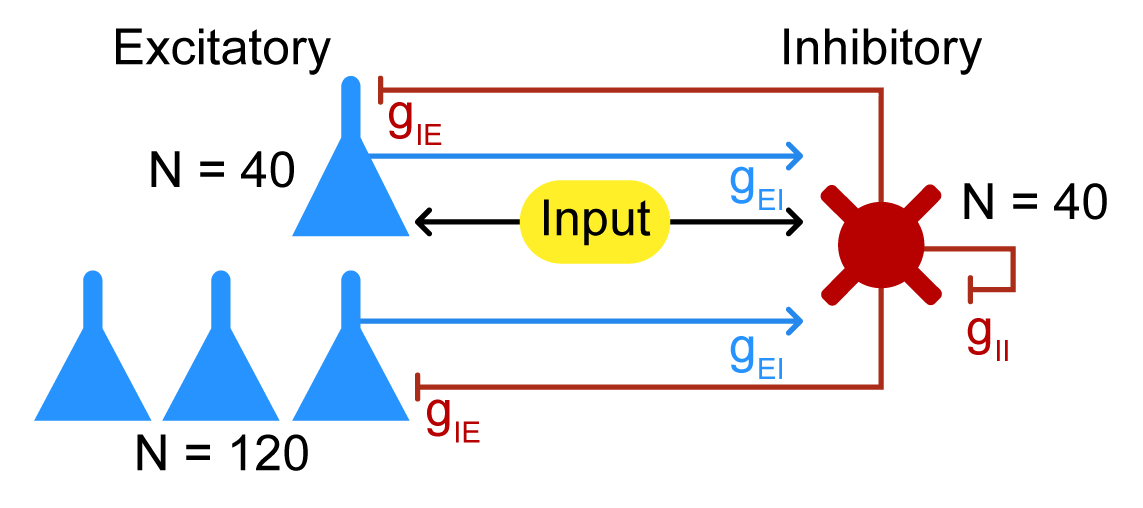

For full details of the model, see Eq. 12-14 on p. 7 of the SI Appendix of Börgers et al. [1]. Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the network structure and which neurons receive the driving input:  Figure 1: Structure of the the PING network.

Figure 1: Structure of the the PING network.

Model Setup

This section sets up the model parameters and the network structure. The network consists of 200 neurons: 40 driven excitatory neurons, 120 other excitatory neurons, and 40 inhibitory neurons. The network is set up as a directed graph with excitatory neurons driving inhibitory neurons and vice versa, with self-inhibition but not self-excitation present.

Import the necessary packages

using Neuroblox

using OrdinaryDiffEq

using Distributions

using Random

using CairoMakieInitialization

Set the random seed to reproduce the plots as shown here exactly. If you want to probe how random variability changes the network, simply omit this line.

Random.seed!(42);Setup the hyperparameters for the PING network simulation. The comments note where these parameters are taken from in the Börgers et al. paper [1] or if they were manually tuned for this particular simulation.

μ_E = 0.8 ## mean of the excitatory neurons' external current, manually tuned from the value on p. 8 of the Appendix

σ_E = 0.15 ## standard deviation of the excitatory neurons' external current, given on p. 8 of the Appendix

μ_I = 0.8 ## mean of the inhibitory neurons' external current, given on p. 9 of the Appendix

σ_I = 0.08 ## standard deviation of the inhibitory neurons' external current, given on p. 9 of the Appendix

NE_driven = 40 ## number of driven excitatory neurons, given on p. 8 of the Appendix. Note all receive constant rather than half stochastic drives.

NE_other = 120 ## number of non-driven excitatory neurons, given in the Methods section

NI_driven = 40 ## number of inhibitory neurons (all driven), given in the Methods section

N_total = NE_driven + NE_other + NI_driven ## total number of neurons in the network

N = N_total ## convenience redefinition to improve the readability of the connection weights

g_II = 0.2 ## inhibitory-inhibitory connection weight, given on p. 8 of the Appendix

g_IE = 0.6 ## inhibitory-excitatory connection weight, given on p. 8 of the Appendix

g_EI = 0.8; ## excitatory-inhibitory connection weight, manually tuned from values given on p. 8 of the AppendixFinally, setup the driving currents. All neurons receive a base external current, and the inhibitory and driven excitatory populations receive a second external stimulus current. The undriven excitatory neurons receive a small addition to the base current in lieu of the stochastic current in the original implementation. There is also an external inhibitory bath for the inhibitory neurons - for the importance of this bath see the SI Appendix of Börgers et al. [1]. These currents are specified as distributions using the syntax from Distributions.jl. The advantage to this is that a distribution can be given to a call of rand() and the random number will be drawn from the specified distribution. We'll use this call during the neuron creation step below.

I_base = Normal(0, 0.1) ## base external current for all neurons

I_driveE = Normal(μ_E, σ_E) ## External current for driven excitatory neurons

I_driveI = Normal(μ_I, σ_I) ## External current for driven inhibitory neurons

I_undriven = Normal(0, 0.4) ## Additional noise current for undriven excitatory neurons. Manually tuned.

I_bath = -0.7; ## External inhibitory bath for inhibitory neurons - value from p. 11 of the SI AppendixCreating a Network in Neuroblox

Creating and running a network of neurons in Neuroblox consists of three steps: defining the neurons, defining the graph of connections between the neurons, and simulating the system represented by the graph.

Define the Neurons

The neurons from Börgers et al. [1] are implemented in Neuroblox as PINGNeuronExci and PINGNeuronInhib. We can specify their initial current drives and create the neurons as follows:

exci_driven = [PINGNeuronExci(name=Symbol("ED$i"), I_ext=rand(I_driveE) + rand(I_base)) for i in 1:NE_driven] ## In-line loop to create the driven excitatory neurons, named ED1, ED2, etc.

exci_other = [PINGNeuronExci(name=Symbol("EO$i"), I_ext=rand(I_base) + rand(I_undriven)) for i in 1:NE_other] ## In-line loop to create the undriven excitatory neurons, named EO1, EO2, etc.

exci = [exci_driven; exci_other] ## Concatenate the driven and undriven excitatory neurons into a single vector for convenience

inhib = [PINGNeuronInhib(name=Symbol("ID$i"), I_ext=rand(I_driveI) + rand(I_base) + I_bath) for i in 1:NI_driven]; ## In-line loop to create the inhibitory neurons, named ID1, ID2, etc.NOTE: If you want to explore the details of these Bloxs, try typing

?PINGNeuronExcior?PINGNeuronInhibin your Julia REPL to see the full details of the blocks. If you really want to dig into the details, type@edit PINGNeuronExci()to open the source code and see how the equations are written.

Define the Graph of Network Connections

This portion illustrates how we go about creating a network of neuronal connections.

g = MetaDiGraph() ## Initialize the graph

for ne ∈ exci

for ni ∈ inhib

add_edge!(g, ne => ni; weight=g_EI/N) ## Add the E -> I connections

add_edge!(g, ni => ne; weight=g_IE/N) ## Add the I -> E connections

end

end

for ni1 ∈ inhib

for ni2 ∈ inhib

add_edge!(g, ni1 => ni2; weight=g_II/N); ## Add the I -> I connections

end

endAlternative Graph Creation

If you are creating a very large network of neurons, it may be more efficient to add all of the nodes first and then all of the edges via an adjacency matrix. To illustrate this, here is an alternative to the graph construction we have just performed above that will initialize the same graph.

g = MetaDiGraph() ## Initialize the graph

add_blox!.(Ref(g), [exci; inhib]) ## Add all the neurons to the graph

adj = zeros(N_total, N_total) ## Initialize the adjacency matrix

for i ∈ 1:NE_driven + NE_other

for j ∈ 1:NI_driven

adj[i, NE_driven + NE_other + j] = g_EI/N

adj[NE_driven + NE_other + j, i] = g_IE/N

end

end

for i ∈ 1:NI_driven

for j ∈ 1:NI_driven

adj[NE_driven + NE_other + i, NE_driven + NE_other + j] = g_II/N

end

end

create_adjacency_edges!(g, adj);Simulate the Network

Now that we have the neurons and the graph, we can simulate the network. We use the system_from_graph function to create a system of ODEs from the graph and then solve it. We choose to solve this system using the Tsit5() solver. If you're coming from Matlab, this is a more efficient solver analogous to ode45. It's a good first try for systems that aren't really stiff. If you want to try other solvers, we'd recommend trying with Vern7() (higher precision but still efficient). If you're really interested in solver choices, one of the great things about Julia is the wide variety of solvers available.

tspan = (0.0, 300.0) ## Time span for the simulation - run for 300ms to match the Börgers et al. [1] Figure 1.

@named sys = system_from_graph(g, graphdynamics=true)

prob = ODEProblem(sys, [], tspan) ## Create the problem to solve

sol = solve(prob, Tsit5(), saveat=0.1); ## Solve the problem and save at 0.1ms resolution.NOTE: Setting

graphdynamics=truewill enable an alternative compilation mode for the neural system. Not every model is compatible with GraphDynamics.jl [4] yet, but for ones that are compatible, it is usually significantly faster to compile. This option will make the biggest difference when you care about very large numbers of neurons, or if you are running the same model with small changes to the number of neurons or connectivity graph many times.

Plotting the Results

Now that we have a whole simulation, let's plot the results and see how they line up with the original figures. We're looking to reproduce the dynamics shown in Figure 1 of Börgers et al. [1]. To create raster plots in Neuroblox for the excitatory and inhibitory populations, it is as simple as:

fig = Figure()

rasterplot(fig[1,1], exci, sol; threshold=20.0, title="Excitatory Neurons")

rasterplot(fig[2,1], inhib, sol; threshold=20.0, title="Inhibitory Neurons")

figThe upper panel should show the dynamics in Figure 1.C, with a clear population of excitatory neurons firing together from the external driving current, and the other excitatory neurons exhibiting more stochastic bursts. The lower panel should show the dynamics in Figure 1.A, with the inhibitory neurons firing in a more synchronous manner than the excitatory neurons.

Conclusion

And there you have it! A complete PING demonstration that reproduces the dynamics of a published paper in a matter of 30 seconds, give or take. Have fun making your own!

Exercise: You might have noticed that the excitatory and inhibitory populations become slightly desynchronized by the end of the simulation, unlike in the original paper. This is because of slight differences in how we implement the excitatory drive and inhibitory bath, which adjusts the overall E/I balance. Try increasing the inhibitory bath or decreasing the percentage of excitatory neurons that receive input and see how this affects the synchrony!

References

[1] Börgers C, Epstein S, Kopell NJ. Gamma oscillations mediate stimulus competition and attentional selection in a cortical network model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 18;105(46):18023-8. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0809511105.

[2] Traub, RD, Miles, R. Neuronal Networks of the Hippocampus. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1991. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511895401

[3] Wang, X-J, Buzsáki, G. Gamma oscillation by synaptic inhibition in a hippocampal interneuronal network model. J. Neurosci., 16:6402–6413, 1996. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06402.1996

[4] Protter, M. (2024). GraphDynamics.jl – Efficient dynamics of interacting collections of modular subsystems (v0.2.2). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14183153